|

Forty Years of Marburg Virus

Werner Slenczka Hans Dieter Klenk

The Journal of Infectious Diseases, Volume 196, Issue Supplement_2, 15 November 2007, Pages S131–S135, https://doi.org/10.1086/520551

Published: 15 November 2007

|

Filoviruses remained largely unknown until 1995,

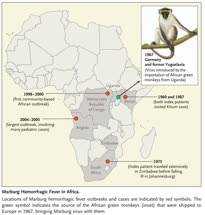

More than 30 years after the discovery of Marburg virus as the causative agent of an outbreak of severe viral hemorrhagic fever in Germany and the former Yugoslavia in 1967, the long forgotten pathogen has struck twice in the recent past, leaving no doubt about its survival in nature or its pathogenic potential.

The first strike came in 1998 (and lasted until 2000), when Marburg virus hit a gold-mining community in the northeastern region of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, as discussed by Bausch and colleagues in this issue of the Journal (pages 909–919).

A second outbreak followed in northern Angola in 2004 and 2005.1 Between 1967 and 1998, Marburg virus infections were rare events, with only three incidences reported, each involving either a single case (Ken ya, 1987) or an index case plus the infection of a traveling companion, medical personnel, or both (Zimbabwe–South Africa, 1975, and Kenya, 1980) (see map).1

The 1998 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo represented the first community-based Marburg virus outbreak in Africa. It occurred in an area that was geographically close to previously reported Marburg virus activity, but it was unique among reported filovirus outbreaks in that continuous infections occurred over a period of almost two years. Bausch et al. describe a seasonal pattern to that event, with transmission beginning in October and November and peaking inin January and February.

|

|

|

|

The filovirus enigma - the natural reservoir remains a mystery

Filoviruses, of which Marburg and Ebola are

the prototypes, are so named because of their long

filamentous appearance when viewed by electron

microscopy. Both Marburg and Ebola viruses have caused

brief but catastrophic self-limiting outbreaks, and Ebola

virus is at present causing numerous deaths in Zaire.

Since the first descriptions of filovirus disease in the

1960s we have learnt a lot about the clinical features but

the natural reservoir remains a mystery

|

|

"The field of emerging pathogens has changed markedly since Karl Johnson spearheaded the effort to adapt the principles of biosafety level 4 biocontainment, originally developed by biodefense workers at Fort Detrick, into the first fully integrated space suit laboratory in 1978."

Forty years have elapsed since the discovery of Marburg virus, and >30 years have elapsed since the discovery of Ebola virus. Filoviruses remained largely unknown until 1995, when Ebola virus re-emerged in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire). The fact that they are highly pathogenic for humans and nonhuman primates, to the point of being the subject of former biological weapons programs, makes Marburg and Ebola viruses feared pathogens worldwide today. Basic research on filovirus biology and pathogenesis has advanced over the past 10 years, leading to the development of reverse-genetics systems, potential treatment strategies, and vaccine candidates. However, because the animal reservoir is still unknown, the clinical course of human infections is not yet adequately understood, and knowledge concerning the immunologic response is incomplete, there is still a long way to go.

In September of 2006, a global symposium on recent advances and future challenges in filovirus research was held in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. The collection of articles in this special supplement of the Journal of Infectious Diseases focuses on Ebola and Marburg viruses, with an emphasis on work that was presented at the Winnipeg meeting. These articles bring us up to date in our understanding of the mechanisms of how filoviruses emerge and re-emerge, the molecular mechanisms of how these viruses replicate and cause disease, and, finally, on the recent progress that has been made in diagnosing filoviral hemorrhagic fever and in developing vaccines and therapies against these lethal microbes. From a public health perspective, among the most important advances are usable rapid and sensitive diagnostics and the development of promising treatment strategies and different vaccine platforms that have demonstrated efficacy in nonhuman primates against Ebola virus, Marburg virus, or both. Because outbreaks of Ebola and Marburg hemorrhagic fever are rare and, to date, restricted to parts of Africa, finding a suitable population in which to systematically evaluate the utility of any countermeasure presents a formidable obstacle and a huge challenge. Studies suggesting that bats are a potential reservoir host for filoviruses are particularly exciting, although this avenue of study needs further confirmation.

Scientific highlights from the meeting and contained in this supplement include detailed elucidation of filovirus biology, involving concepts based on work using recently developed reverse-genetics systems. These systems, which are available in several laboratories, will be instrumental in further dissecting the pathogenesis of filoviral hemorrhagic fever. Finally, this supplement also contains articles that discuss experiences and challenges in Ebola and Marburg disease case and outbreak management that will lead to improved responses in the future. In the past, efforts to study filoviruses have been slowed because these agents require special biocontainment laboratories to safely conduct research. The field of emerging pathogens has changed markedly since Karl Johnson spearheaded the effort to adapt the principles of biosafety level 4 biocontainment, originally developed by biodefense workers at Fort Detrick, into the first fully integrated space suit laboratory in 1978. At the time, the global importance of rare exotic pathogens, such as Ebola and Marburg viruses, and the need for high-level containment were not as apparent as they are today. Fortunately, these early efforts by Johnson and many others to promote and develop these facilities laid the foundation for a landscape that would change. Indeed, the increase in occurrences of outbreaks of emerging and re-emerging viruses over the past decade, coupled with the tragic terrorist events of 11 September 2001, have led to an increased investment in basic research and to the construction of a network of biocontainment laboratories (table 1).

|

|

|