|

The Consequences of a Lab Escape of a Potential Pandemic Pathogen Whatever number we are gambling with, it is clearly far too high a risk to human lives. This Asian bird flu virus research to develop strains transmissible via aerosols among mammals, and perhaps some other PPP research as well, should for the present be banned. We must emphasize that we have been considering only a very small subset of pathogen research. Most pathogen research should proceed unimpeded by unnecessary regulations. |

|

Engineered bat virus stirs debate over risky research Lab-made coronavirus related to SARS can infect human cells.

|

|

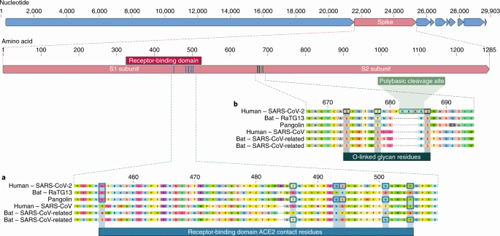

Bat-to-human: spike features determining ‘host jump’ of coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and beyond Both severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) are zoonotic pathogens that crossed the species barriers to infect humans. The mechanism of viral interspecies transmission is an important scientific question to be addressed. These coronaviruses contain a surface-located spike (S) protein that initiates infection by mediating receptor-recognition and membrane fusion and is therefore a key factor in host specificity. In addition, the S protein needs to be cleaved by host proteases before executing fusion, making these proteases a second determinant of coronavirus interspecies infection. Here, we summarize the progress made in the past decade in understanding the cross-species transmission of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV by focusing on the features of the S protein, its receptor-binding characteristics, and the cleavage process involved in priming. |

|

A SARS-like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV underscores the threat of cross-species transmission events leading to outbreaks in humans. Here we examine the disease potential of a SARS-like virus, SHC014-CoV, which is currently circulating in Chinese horseshoe bat populations1. Using the SARS-CoV reverse genetics system2, we generated and characterized a chimeric virus expressing the spike of bat coronavirus SHC014 in a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV backbone. The results indicate that group 2b viruses encoding the SHC014 spike in a wild-type backbone can efficiently use multiple orthologs of the SARS receptor human angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE2), replicate efficiently in primary human airway cells and achieve in vitro titers equivalent to epidemic strains of SARS-CoV. Additionally, in vivo experiments demonstrate replication of the chimeric virus in mouse lung with notable pathogenesis. Evaluation of available SARS-based immune-therapeutic and prophylactic modalities revealed poor efficacy; both monoclonal antibody and vaccine approaches failed to neutralize and protect from infection with CoVs using the novel spike protein. On the basis of these findings, we synthetically re-derived an infectious full-length SHC014 recombinant virus and demonstrate robust viral replication both in vitro and in vivo. Our work suggests a potential risk of SARS-CoV re-emergence from viruses currently circulating in bat populations. |

|

The next SARS? Human-infecting coronaviruses (CoVs), such as SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, are thought to emerge from circulating bat CoVs. To test the emergence potential of SARS-like CoVs currently present in bats, Menachery et al. selected the bat CoV SHC014 (which metagenomics studies identified as a close relative to the epidemic SARS strains) and cloned its spike protein (which mediates viral attachment to host cells) into a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV backbone. The chimeric virus could replicate inside human cell lines and was capable of replicating in mouse lungs. Importantly, currently available therapeutics (monoclonal antibodies and vaccines) failed to protect the mice from viral infection. Finally, the authors synthesized a full-length SHC014 CoV, which was capable of replicating in human cells. These data suggest that CoVs currently circulating in bats have the potential for human emergence. |

|

Novel Coronavirus found in bats in 2018 in Myanmar

|

|

From Jan 10, 2020, we enrolled a family of six patients who travelled to Wuhan from Shenzhen" An ongoing outbreak of pneumonia associated with a novel coronavirus was reported in Wuhan city, Hubei province, China. Affected patients were geographically linked with a local wet market as a potential source. No data on person-to-person or nosocomial transmission have been published to date.

|

|

The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2 SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus known to infect humans; SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 can cause severe disease, whereas HKU1, NL63, OC43 and 229E are associated with mild symptoms6. Here we review what can be deduced about the origin of SARS-CoV-2 from comparative analysis of genomic data. We offer a perspective on the notable features of the SARS-CoV-2 genome and discuss scenarios by which they could have arisen. Our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus. |

|

Coronavirus origins: genome analysis suggests two viruses may have combined In addition, these genomic comparisons suggest that the SARS-Cov-2 virus is the result of a recombination between two different viruses, one close to RaTG13 and the other closer to the pangolin virus. In other words, it is a chimera between two pre-existing viruses. |

|

By Jan 2, 2020, 41 admitted hospital patients had been identified as having laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infection. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. 27 (66%) of 41 patients had been exposed to Huanan seafood market. |

|

The Case Is Building That COVID-19 Had a Lab Origin But one other troubling possibility must be dispensed with. It follows from the fact that the epicentre city, Wuhan (pop. 11 million), happens to be the global epicentre of bat coronavirus research (e.g. Hu et al., 2017). |

|

Did this virus come from a lab? Maybe not — but it exposes the threat of a biowarfare arms race Dangerous pathogens are captured in the wild and made deadlier in government biowarfare labs. Did that happen here?

|

|

Possible Bat Origin of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 We showed that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is probably a novel recombinant virus. Its genome is closest to that of severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronaviruses from horseshoe bats, and its receptor-binding domain is closest to that of pangolin viruses. Its origin and direct ancestral viruses have not been identified. |

|

The divergence between SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 might be overestimated due to the extensive RNA modification Aim: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has spread throughout the world. There is urgent need to understand the phylogeny, divergence and origin of SARS-CoV-2. Materials & methods: A recent study claimed that there was 17% divergence between SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 (a SARS-related coronaviruses) on synonymous sites by using sequence alignment. We re-analyzed the sequences of the two coronaviruses with the same methodology. Results: We found that 87% of the synonymous substitutions between the two coronaviruses could be potentially explained by the RNA modification system in hosts, with 65% contributed by deamination on cytidines (C-T mismatches) and 22% contributed by deamination on adenosines (A-G mismatches). Conclusion: Our results demonstrate that the divergence between SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 has been overestimated. |

|

No credible evidence supporting claims of the laboratory engineering of SARS-CoV-2 Currently, there are speculations, rumours and conspiracy theories that SARS-CoV-2 is of laboratory origin. Some people have alleged that the human SARS-CoV-2 was leaked directly from a laboratory in Wuhan where a bat CoV (RaTG13) was recently reported, which shared ∼96% homology with the SARS-CoV-2 [4]. However, as we know, the human SARS-CoV and intermediate host palm civet SARS-like CoV shared 99.8% homology, with a total of 202 single-nucleotide (nt) variations (SNVs) identified across the genome [6]. Given that there are greater than 1,100 nt differences between the human SARS-CoV-2 and the bat RaTG13-CoV [4], which are distributed throughout the genome in a naturally occurring pattern following the evolutionary characteristics typical of CoVs, it is highly unlikely that RaTG13 CoV is the immediate source of SARS-CoV-2. The absence of a logical targeted pattern in the new viral sequences and a close relative in a wildlife species (bats) are the most revealing signs that SARS-CoV-2 evolved by natural evolution. A search for an intermediate animal host between bats and humans is needed to identify animal CoVs more closely related to human SARS-CoV-2. There is speculation that pangolins might carry CoVs closely related to SARS-CoV-2, but the data to substantiate this is not yet published (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00364-2).

|

|

Full-genome evolutionary analysis of the novel corona virus (2019-nCoV) rejects the hypothesis of emergence as a result of a recent recombination event Our analysis suggests that the 2019-nCoV although closely related to BatCoV RaTG13 sequence throughout the genome (sequence similarity 96.3%), shows discordant clustering with the Bat_SARS-like coronavirus sequences. Specifically, in the 5′-part spanning the first 11,498 nucleotides and the last 3′-part spanning 24,341–30,696 positions, 2019-nCoV and RaTG13 formed a single cluster with Bat_SARS-like coronavirus sequences, whereas in the middle region spanning the 3′-end of ORF1a, the ORF1b and almost half of the spike regions, 2019-nCoV and RaTG13 grouped in a separate distant lineage within the sarbecovirus branch.

|

|

New Evidence the US Did Bring COVID-19 to Wuhan During the Military Games WUHAN OUTBREAK: CHINA DEMANDS AN HONEST ACCOUNTING

|

|

"Aside from RaTG13, Pangolin-CoV is the most closely related CoV to SARS-CoV-2" - Probable Pangolin Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Associated with the COVID-19 Outbreak An outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) began in the city of Wuhan in China and has widely spread worldwide. Currently, it is vital to explore potential intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV-2 to control COVID-19 spread. Therefore, we reinvestigated published data from pangolin lung samples from which SARS-CoV-like CoVs were detected by Liu et al. [1]. We found genomic and evolutionary evidence of the occurrence of a SARS-CoV-2-like CoV (named Pangolin-CoV) in dead Malayan pangolins. Pangolin CoV is 91.02% and 90.55% identical to SARS-CoV-2 and BatCoV RaTG13, respectively, at the whole genome level. Aside from RaTG13, Pangolin-CoV is the most closely related CoV to SARS-CoV-2. The S1 protein of Pangolin-CoV is much more closely related to SARS-CoV-2 than to RaTG13. Five key amino acid residues involved in the interaction with human ACE2 are completely consistent between PangolinCoV and SARS-CoV-2, but four amino acid mutations are present in RaTG13. Both Pangolin-CoV and RaTG13 lost the putative furin recognition sequence motif at S1/S2 cleavage site that can be observed in the SARS-CoV-2. Conclusively, this study suggests that pangolin species are a natural reservoir of SARS-CoV-2-like CoVs |

|

State Department cables warned of safety issues at Wuhan lab studying bat coronaviruses Two years before the novel coronavirus pandemic upended the world, U.S. Embassy officials visited a Chinese research facility in the city of Wuhan several times and sent two official warnings back to Washington about inadequate safety at the lab, which was conducting risky studies on coronaviruses from bats. The cables have fueled discussions inside the U.S. government about whether this or another Wuhan lab was the source of the virus — even though conclusive proof has yet to emerge.

|

|

"...between Oct. 7 and Oct. 24, no mobile phone data was recorded coming from part of the site thought to be the high-security National Biosafety Laboratory..." NBC added that US and UK intelligence agencies are examining a privately compiled report suggesting that between Oct. 7 and Oct. 24, no mobile phone data was recorded coming from part of the site thought to be the high-security National Biosafety Laboratory. The site was previously a source of frequent mobile phone activity prior to Oct. 7, leading the report’s authors to speculate that a “hazardous event” might have taken place some time between Oct. 6 and Oct. 11. In the intelligence report, seen by NBC, mobile data also suggested that police roadblocks were put in place between Oct. 14 and Oct. 19. But there are doubts over the report’s veracity and the identity of its authors, with experts saying it may be based solely on commercially available mobile phone data, which would be limited in its scope. Ruaridh Arrow, head of NBC News London’s Verification Unit, also urged caution, saying the data “may be misleading.” |

|

Claims arose "Huang Yanling", a Wuhan lab worked was “patient zero” but Huang left in 2015, was in good health and never had covid-19. Prof Ebright said he has seen evidence that scientists at the Centre for Disease Control and the Institute of Virology studied the viruses with only “level 2” security — rather than the recommended level 4 – which “provides only minimal protection against infection of lab workers,” the report said.

|

|

Most of us have heard that this virus "started" in a wildlife market in Wuhan. But the source of the virus - an animal with this pathogen in its body - was not found in the market. "The initial cluster of infections was associated with the market - that is circumstantial evidence," explained Prof James Wood from the University of Cambridge.

|

|

It might have been the US army representatives to the Military World Games who brought the novel coronavirus to Wuhan in October 2019 Chinese netizens and experts urge the US authority to release health and infection information of the US military delegation which came to Wuhan for the Military World Games in October to end the conjecture about US military personnel bringing COVID-19 to China.

|

|

The Long History of Accidental Laboratory Releases of Potential Pandemic Pathogens Is Being Ignored In the COVID-19 Media Coverage Many people are dismissing the possibility that the COVID-19 pandemic might have come from a lab. It is possible that they are unaware of the frequency of biohazards escaping from laboratories. |

|

Telemetry data from the Wuhan BSL4 lab

|

|

The report — obtained by the London-based NBC News Verification Unit — says there was no cellphone activity in a high-security portion of the Wuhan Institute of Virology from Oct. 7 through Oct. 24, 2019, and that there may have been a "hazardous event" sometime between Oct. 6 and Oct. 11.

|

|

"...a new virus..." HONG KONG — Chinese researchers say they have identified a new virus behind an illness that has infected dozens of people across Asia, setting off fears in a region that was struck by a deadly epidemic 17 years ago.

|

|

Scientists in China sequenced the virus’s genome and made it available on Jan. 10, just a month after the Dec. 8 report of the first case of pneumonia from an unknown virus in Wuhan. In contrast, after the SARS outbreak began in late 2002, it took scientists much longer to sequence that coronavirus. It peaked in February 2003 — and the complete genome of 29,727 nucleotides wasn’t sequenced until that April. |

|

"... on January 20, Chinese President Xi Jinping made his first public statement on the outbreak..." “From that perspective, it looks like China is reporting now,” Hoffman added, noting there’s no evidence, at this time, that they’re withholding information. “But you always need to be worried: When one source isn’t as forthcoming from the beginning, you never know later on.” And if this virus continues to move at a dizzying speed, the question of whether China mischaracterized what they knew about the virus will become even more urgent.

|

|

Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants are circulating globally. Several new variants emerged in the fall of 2020, most notably:

|