By Rob Brown

BBC World Service

18 July 2014

Nearly 40 years ago, a young Belgian scientist travelled to a remote part of the Congolese rainforest - his task was to help find out why so many people were dying from an unknown and terrifying disease.

In September 1976, a package containing a shiny, blue thermos flask arrived at the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium.

Working in the lab that day was Peter Piot, a 27-year-old scientist and medical school graduate training as a clinical microbiologist.

"It was just a normal flask like any other you would use to keep coffee warm," recalls Piot, now Director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

But this thermos wasn't carrying coffee - inside was an altogether different cargo. Nestled amongst a few melting ice cubes were vials of blood along with a note.

"When we opened the thermos, we saw that one of the vials was broken and blood was mixing with the water from the melted ice," says Piot.

Two weeks later Piot, who had never been to Africa before, was on a flight to Kinshasa. "It was an overnight flight and I couldn't sleep. I was so excited about seeing Africa for the first time, about investigating this new virus and about stopping the epidemic."

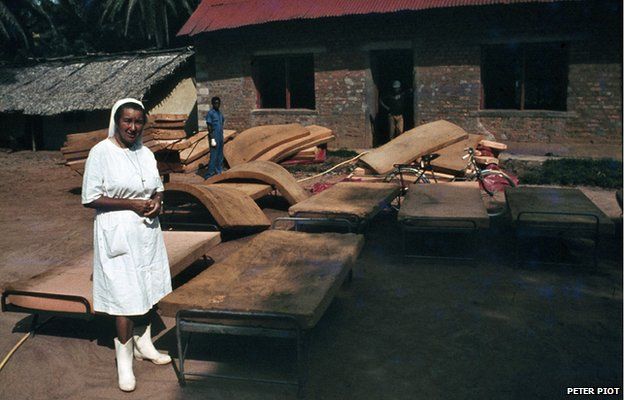

The journey didn't end in Kinshasa - the team had to travel to the centre of the outbreak, a village in the equatorial rainforest, about 1,000km (620 miles) further north.

When the C-130 landed in Bumba, a river port situated on the northernmost point of the Congo River, the fear surrounding the mysterious disease was tangible. Even the pilots didn't want to hang around for long - they kept the airplane's engines running as the team unloaded their kit.

"As they left they shouted 'Adieu,'" says Piot. "In French, people say 'Au Revoir' to say 'See you again', but when they say 'Adieu' - well, that's like saying, 'We'll never see you again.'"